Bikini Atoll

THE HISTORY OF NUCLEAR TESTING ON BIKINI ATOLL

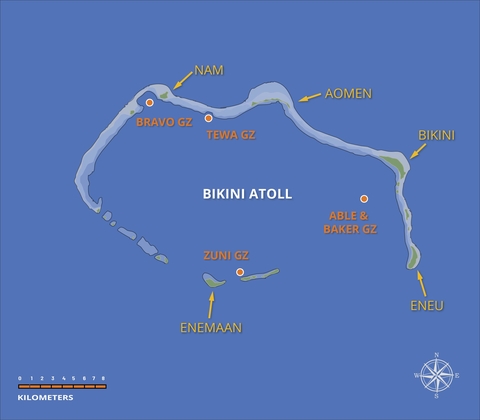

Bikini Atoll forms part of Ralik chain of atolls in the northern Marshall Islands and is located about 305 kilometers east of Enewetak Atoll at about 11°36′N 165°23′E. The atoll consists of 23 named islands with a combined land surface area of just over 5.5 square kilometers distributed around a 70-kilometer-long oval-shaped reef. Bikini Atoll has a deep-water central lagoon of approximately 630 square kilometers with a maximum depth of around 65 meters.

The United States conducted 23 near-surface nuclear tests on Bikini between 1946 and 1958 with a combined explosive yield of 78.6Mt, equivalent to 78.7 million tons of high explosives. The nuclear test program began with Operations Crossroads in July 1946. In preparation for Operation Crossroads, the local population were persuaded by the U.S. military to relocate to Rongerik Atoll, about 200 kilometers east of Bikini, based on the belief that they would be able to return to their homeland.

Operation Crossroads was conducted under a great deal of fanfare and has been described as one of the most publicized, well documented and reported peacetime military exercises in history. Those invited to observe the tests included congressmen, journalists, scientists, military officers, and foreign observers including a Soviet Commissar of Internal Affairs. Operation Crossroads was designed to explore the effectiveness of atomic weapons for engagement of naval forces. Animal experiments were also conducted. The 21-kT Able device was dropped by a B-29 bomber on 30 June 1946 and detonated at a height of about 161 meters above a fleet of over 70 naval target ships moored in the lagoon. The nuclear device missed its intended target by over 450 meters, reportedly resulting in less damage to target vessels than anticipated.

The second test, code named Baker, was conducted on 24 July 1946 from a device suspended underwater at a depth of around 28 meters. The 21-kT Baker blast lifted an enormous column of water into the air and caused very significant contamination of the surface ships. One ship was vaporized. Eight vessels either sunk or capsized and many other vessels suffered extensive damage. A third nuclear test was canceled.

The most significant contaminating event in the Marshall Islands nuclear test campaign and the highest yield atmospheric nuclear test ever conducted by the United States involved the detonation of a high-energy thermonuclear on Bikini Atoll on 1 March of 1954. This ground-surface test was code named Bravo and had an estimated explosive yield of 15 Mt. Prior to Bravo, little consideration was given to the potential health and ecological impacts of fallout contamination beyond the immediate ‘boundaries’ of the test sites. However, regional fallout from the Bravo test caused widespread fallout contamination over Bikini Atoll and forced the evacuation of Marshallese people living on Rongelap and Utrōk Atolls.

MOVEMENT OF THE BIKINI PEOPLE

The history behind the relocation of the people of Bikini and their heroic struggle in the nuclear age is a sorrowful yet very compelling story. Towards the end of World War II and following cessation of hostilities in the Pacific, the U.S Navy administrated the Marshall Island as Occupied Enemy Territory.

In February of 1946, obligated by Marshallese culture bound by tradition and a harmonious fellowship for mankind, the people of Bikini agreed to a request by then-appointed U.S. military governor of the Marshall Islands to temporarily leave their homeland so the United States could begin testing of atomic weapons. They were told that their land was needed for "the good of mankind and to end all world wars.”

A few weeks later, the U.S. Navy relocated the 167 people living on Bikini to Rongerik Atoll. Rongerik Atoll was a small uninhabited atoll about 1/6th the size of Bikini with very marginal fishing and agricultural resources. Cast away on Rongerik and out of view, life proved to be very harsh on the people of Bikini. The atoll soil was found to be less productive than Bikini for growing food crops and fish taken from the lagoon were fewer in number and had a history of being poisonous. Also, although Rongerik was occasionally visited by people from Rongelap Atoll, there was a traditional Marshallese belief that the atoll was haunted by evil spirits.

President Truman recognized the need for civilian authority over the Occupied Enemy Territories and in November 1946 proposed to the United Nations that former mandated islands in the Pacific be placed under a United Nations Trusteeship. In July 1947, the Marshall Islands was formally placed under a United Nations trusteeship agreement as part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI) with the United States as the Administrating Authority.

Around the same time, U.S. medical officers and investigators dispatched to Rongerik Atoll reported back that the atoll had an inadequate supply of food and water, and that the inhabitants should be relocated without delay. In the proceeding months, the situation on Rongerik grew worse. It was reported that inhabitants were suffering from severe malnutrition and on the verge of starvation. In March 1948, after spending two long years on Rongerik, the Bikinians were relocated to Kwajalein Atoll where they were housed in tents adjacent to a busy runway used by the U.S. military. After much deliberation, the 184 Bikinians living on Kwajalein Atoll were again relocated. Of potential places to live they chose Kili Island in the southern Marshalls as their new temporary home. Kili was very small 80-hectare volcanic island that lacked the food resources, a natural lagoon and safe anchorage to effectively sustain a community-based subsistence lifestyle. However, what was of paramount importance to the Bikinians at that time was to find a location that was uninhabited. The Bikinians believed that use of an uninhabited atoll would help allow the community to retain their cultural identity while avoiding possible conflicts with any existing inhabitants ruled by a traditional chief, or iroij.

Survival on Kili meant the Bikinians grew dependent on regular deliveries of imported food and a culture of subsistence living rapidly lost. Also, Kili Island had little to offer in terms of any revenue earning potential from sale of copra (dried coconut) or other marketable commodities. A few families from Kili established a satellite community on Jaluit Atoll during the mid-1950s to produce copra. These efforts were short lived. Those families who moved to Jaluit Atoll were forced to move back to Kili after a series of typhoons hit the southern Marshalls in late 1957-and early 1958, damaging available village housing and food tree-crops and sinking the local atoll government’s resupply vessel. In general, there has been a long history of issues associated with the sporadic resupply schedules to Kili Island including difficulties offloading supplies in heavy seas. Food shortages were common.

Beginning in 1967, U.S. government agencies began directing efforts towards the possible repatriation of the people of Bikini back onto their home atoll. The atoll was subsequently resurveyed, and an ad hoc committee convened by the Atomic Energy Commission to consider the resettlement of Bikini. Prompted by the committee’s recommendations as conveyed by the Atomic Energy Commission through the Secretary of the Interior as the entrusted administrator for the Trust Territories, President Lyndon B. Johnson publicly announced in August of 1968 that his administration would resettle the people of Bikini on their home atoll. In February 1969, under the authority of Atomic Energy Commission and the U.S. Department of Defense, a general cleanup program was initiated on Bikini to remove radioactive debris and other physical hazards. The second phase of the reclamation project involved the planting of coconut and other food tree-crops on Bikini and Eneu Islands, construction of concrete houses and eventual relocation of the community. These efforts were entrusted to Trust Territory officials but proceeded slowly due the lack of logistical support and availability of heavy equipment. About 40 people began living on Eneu Island in support of cleanup, construction, and agricultural projects.

At that time, it was believed that the main source of internal radiation exposure to the resident population would come from dietary consumption of strontium-90 contained in locally grown foods crops. That would later prove to be false. As new and conflicting information became to surface about radiological conditions on Bikini, the local atoll council voted against resettling Bikini but allowed individuals to make their own determination about moving back to Bikini. The planting of the coconut trees on Bikini and Eneu Islands was finally completed in 1972. Three extended families returned to Bikini and, along with the people living on Eneu Island, moved into the newly constructed homes on Bikini Island.

The number of people living on Bikini slowly increased over the years. By 1975, and as newly planted food tree crops began to bear fruit, radiological monitoring studies began to substantiate claims that Bikini was not safe for resettlement. The Atomic Energy Commission declared locally grown foods and coconut crabs were too radioactive for human consumption. Unsafe levels of radioactive contamination were reported in well water samples, and measurable quantities of plutonium were detected in urine bioassay samples analyzed by Brookhaven National Laboratory. Conflicting data and information on the potential health risk posed by residual fallout contamination in the environment, led the people of Bikini to file a successful lawsuit in U.S. federal court demanding more complete scientific studies be conducted of radiological conditions on Bikini and the northern Marshall Islands. The U.S. agreed to conduct an aerial survey of the Marshall Islands in December 1975, but it would be three long years before U.S. agencies could reach agreement on its implementation. Meanwhile, the resettled Bikinians remained on their home atoll.

History was about to repeat itself. By 1997, the amount of cesium-137 taken up by the people residing on Bikini had reportedly increased by a factor of 11-fold. The U.S. Department of Energy issued a call to provide imported foods to the community and advised residents to limit their consumption of coconut crabs. In April 1978, whole body count measurements revealed that many residents on Bikini had acquired body burdens of cesium-137 levels more than the maximal permissible level. Alarmed by these findings, the U.S. Department of Interior prompted announced plans to evacuate people from Bikini. The inhabitants of Bikini packed up their possessions and were shipped off to Ejit Island on Majuro Atoll. A few families returned to Kili. Kili Island has remained the principal temporary home of the people of Bikini ever since but the cultural identity and traditions of the Bikinians have been securely eroded over the decades as families scattered across the Marshall Islands or moved to Hawaii and other parts of the United States.

As of March 2016, there were about 5,400 Bikini islanders. About 800 Bikinians live on Kili, 2,550 on Majuro, 300 on Ejit, and 350 in other parts of the Marshall Islands. About 1,400 Bikinians live in the United States or other countries. Today, Bikini Atoll largely remains uninhabited. Local on-island infrastructure is maintained by a small caretaker workforce. The atoll is occasionally visited by divers, ecotourists and water sports enthusiasts on organized boat charters. Yachts are also known to pass through the area and seek anchorage. Bikini is classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is considered one the most spectacular shipwreck diving sites in the world. It is one of only 3 sites where you can dive on a sunken aircraft carrier (the USS Saratoga).

The future resettlement of Bikini Atoll remains very uncertain. The Bikini leadership continue to lobby the U.S. Congress for additional funding to provide necessary infrastructure development and for full cleanup and rehabilitation of their entire atoll.

ENVIRONMENTAL CHARACTERIZATION ON BIKINI

Through the 1980s and 1990s, scientists from the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory developed an extensive database of environmental measurements for Bikini Atoll, especially for soils and vegetation growing on Bikini and Eneu Islands. These monitoring surveys were used to develop predictive dose assessments of exposure of hypothetical resident populations to residual fallout contamination in the marine and terrestrial environments. Wherever possible, the surveys involved direct measurements of radionuclide concentrations in soil and associated food-crop products, as well as air, water, fish, and resident marine organisms. These data and information were essential in helping identify the key radionuclides and radiological exposure pathways in the Marshall Islands, and in assisting the U.S. Department of Energy and the Kili-Bikini-Ejit Local Government in making more informed decisions about future resettlement and the need for cleanup of the atoll. During this period, predictive dose assessments for Bikini, Enewetak, Rongelap, and Utrōk Atolls clearly demonstrated that the most significant pathway for human exposure to residual fallout contamination in the environment was ingestion of cesium-137 contained in locally grown tree food crops such as coconut, breadfruit, and Pandanus.

Under the direction of the U.S Department of Energy and upon request from RMI officials and Kili-Bikini-Ejit Local Government, Livermore scientists continue to monitor the environment at Bikini with added emphasis on providing data and information in support of marine and terrestrial resource development activities. Persistent and elevated levels of fallout contamination found in bottom sediments of the lagoon formed a long-term source-term for solubilization into the water column and assimilation into fish, aquatic plants, and other marine organisms. This is especially true of particle reactive radionuclides such as plutonium. Sediments contained in deepwater bomb craters inside the lagoon also appear to supply a measurable flux (by advection) of water-soluble fallout radionuclides, including cesium-137 (strontium-90) and iodine-129, into the overlying water column.

Updated data and information is being formulated on any radiological implications associated with on-going and/or potential new resource development activities on Bikini, to include sports diving and fishing, ecotourism, and fish aquaculture projects. Answers will be presented on what it means for visitors to spend a short period of time walking around the islands; consuming local fish, clam tissues or other types of marine biota and locally grown terrestrial foods; and/or diving on the shipwrecks. Also, the local government periodically collects pantry foods such as fish, lobster, sea birds, and coconut crabs from Bikini to distribute to the community for special events. The workforce on Bikini is also known to consume some local foods and may be more at risk compared with all other cohort populations groups. If these practices are to be continued and/or expanded upon with development of aquaculture or other commercial projects, we strongly recommend that a dose/risk assessment on consumption of pantry foods and short-term visitations to Bikini be conducted at least once every 3 to 5 years. Also, the Kili-Bikini-Ejit Local Government is giving consideration to developing support housing and hotel accommodation on Bikini and/or Eneu Island as part of a long-term economic development plan for Bikini Atoll. Scientists from the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory stand ready to provide advice and assistance as needed.

REMEDIATION EFFORTS

Why does cesium-137 uptake in food plants play such an important role in contributing to radiation exposure in the Marshall Island?

Continuing research on the fate and transport of cesium-137 in coral soil shows that this phenomenon is largely driven by the unique nature of carbonate (coral atoll) soils. Coral soils are deficient in potassium, an essential nutrient for plant growth. Cesium (Cs) is an alkali metal and has chemical and physical properties like potassium. Locally grown plants in the Marshall Islands attempt to satisfy their nutritional requirements by taking up soil cesium as a surrogate element, including any available radiocesium (137Cs). Similarly, coral soils are known to contain very low concentrations of aluminosilicate (clay) materials. The presence of clay material in soil helps suppress the bioavailability of cesium-137 for soil-to-plant uptake by helping fix cesium ions inside the crystal lattice structure of the clays. In this instance, the lack of potassium combined with the low clay mineral content of coral soil both tend to enhance the uptake (or bioavailability) of soil 137Cs into food plants in comparison with other soil types around the globe.

Knowledge of the unique behavior of cesium-137 in potassium-poor coral soil environments has also been instrumental in helping guide remediation experiments to reduce the dose contribution from exposure to residual fallout contamination in the environment, and build an effective and meaningful individual radiological monitoring program based on whole-body counting of internally deposited cesium-137.

Long-term field experiments on Bikini show that treating agricultural areas with potassium fertilizer (KCl) is an effective and practical method for reducing the uptake of cesium-137 into locally grown food crops. This approach also increased the growth rate and productivity of some food crops with essentially no adverse environmental impacts. Also, the on-going research program in the Marshall Islands has clearly demonstrated that soil cesium-137 is becoming less availability for plant uptake over time. The estimated effective half-life of cesium-137 into food plants is around 8.5 years. This compares with the radiological half-life of cesium-137 of 30 years. These rapidly improving radiological condition combined with full implementation of proposed cleanup measures would appear to show that the cleanup and resettlement of Bikini Atoll may become much more plausible and cost effective. Once resettlement begins, we recommend establishing a radiological surveillance program on Bikini Island based on whole-body counting and, if required, plutonium urinalysis. In this way, the Kili-Bikini-Ejit Local Government and the people of Bikini can be assured that radiological conditions on the islands remain at or below applicable safety standards, and the United States Government can avoid mistakes of the past.